We are gaining great traction over at the Center for Carbon Removal. Make sure to check out our blog and follow us on Twitter @CarbonRemoval, and continue the carbon removal conversation there!

Author: Noah

Exciting blog news: Everything and the Carbon Sink is Moving to the Center for Carbon Removal!

It is with great pleasure that I announce that this blog will be moving to the Center for Carbon Removal at: http://www.centerforcarbonremoval.org/blog!

The Center for Carbon Removal is a new environmental NGO dedicated to accelerating the development of carbon removal solutions (many of which have been featured here on this blog!). Carbon-removing farms, energy systems, buildings, and manufacturing facilities — among many others — hold enormous potential to transform the global economy to be more sustainable. The Center for Carbon Removal is a first-of-its-kind effort to unlock this potential through research and analysis, event organization, and information/communication campaigns focusing on carbon removal solutions.

My posting frequency has been slower than I’d like over the past few months as I’ve worked with an amazing team of advisers and partners to get the Center ready for launch, but our team at the Center plans to post content with greater frequency on the new site. What’s more, out website (www.centerforcarbonremoval.org) aims to provide our community with a growing range of tools to continue the dialogue on carbon removal, discover new information about promising carbon removal solutions, and share information with other communities that are passionate about sustainability, fighting climate change, and cleantech entrepreneurship.

So please check out our new site, give us feedback and engage in conversation, share resources you think are useful, and help us grow our community by spreading the word on carbon removal via Twitter (@CarbonRemoval) and Facebook!

12 things I believe about carbon removal: June 2015

Next month marks the one year anniversary of Everything and the Carbon Sink. Having watched the carbon removal field develop over the last year, I’ve decided its time to synthesize my views on the topic, in hopes of revisiting and updating these beliefs as I get new information to strengthen/disabuse me of these notions. Without further ado, 12 things I believe about carbon removal:

- Preventing catastrophic climate change is a moral and economic imperative.

- Preventing catastrophic climate change requires that we limit the global mean temperature increase to 2 degrees C from pre-industrial levels.

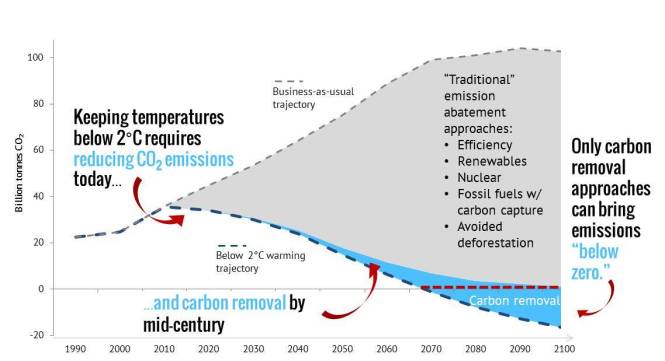

- A portfolio of traditional greenhouse gas mitigation measures (renewable energy, energy efficiency, avoided deforestation, etc.) and a portfolio of gigatonne-scale carbon removal solutions (both biological and chemical) are necessary to limit temperature increases to 2 degrees C if we also want to avoid geoengineering.

- In the future, the portfolio of large-scale carbon removal solutions will include: re/afforestation, ecosystem restoration, carbon sequestering agriculture, biochar, bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration, direct air/seawater capture and sequestration, mineral weatherization, “blue carbon” strategies, and likely other techniques not yet proposed/published.

- Geoengineering is worth avoiding, as its risks outweigh its potential benefits.

- Developing sustainable and economically-viable carbon removal solutions will require significant investments in research and development.

- Once developed, commercializing promising carbon removal solutions will require the development of markets that demand carbon removal — carbon removal as a co-benefit alone will not be enough to reach gigatonne scale removal levels.

- In order to catalyze development of carbon removal technologies and markets, leaders from industry, policy, NGOs, philanthropies and the general public need to engage in dialogues about the best ways to develop carbon removal solutions — information and discussion is needed before effective action occurs.

- Armed with information about the opportunities and challenges of carbon removal, a broad coalition of business and environmental interests will emerge to support the development of carbon removal solutions — no entrenched interest gains from keeping carbon in the air, so no entrenched interests have an economic incentive to fight the development of carbon removal solutions.

- Opponents to carbon removal will mostly object to the specifics of how carbon removal is accomplished/implemented, not to the overall need for carbon removal to fight climate change.

- The few opponents that do object to carbon removal writ large will do so on grounds that A) carbon removal will lead to a moral hazard that delays action to reduce emissions and/or B) carbon removal solutions are too expensive and slow working to implement at scale.

- Carbon removal solutions will not lead to moral hazard around reducing emissions, as carbon removal solutions will not develop quickly enough for companies to continue emissions at large scale so long as they remove more than they emit, rendering the moral hazard argument largely a distraction.

“Pre-pay” carbon policy: how carbon removal enables regulatory alternatives

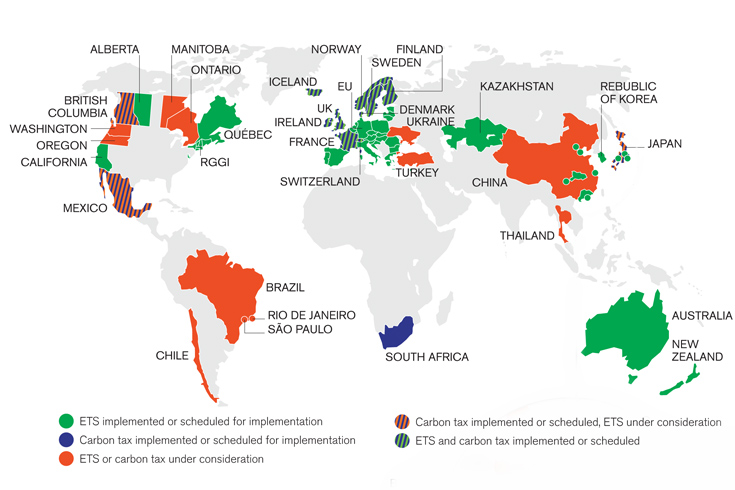

Today, there is growing bipartisan support for governments across the world to price carbon emissions. Moving from theory to practice, however, has proven challenging, as the two leading approaches to pricing carbon, carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs, only cover about 12% of all carbon emissions globally today.

Above: the World Bank State & Trends Report Charts Global Growth of Carbon Pricing — many jurisdictions are considering carbon pricing programs, but only a fraction of all emissions are currently covered under existing regulations.

Besides carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs, few other approaches to carbon pricing have been proposed. But the development of carbon removal solutions – i.e. processes that remove and sequester carbon from the atmosphere – could provide an opportunity for a new type of “pre-pay” carbon pricing system that avoids many of the pitfalls of today’s carbon pricing proposals.

A “pre-pay” carbon policy might work something like this: before a company extracts a ton of carbon from the ground (be it in the form of oil, natural gas, coal, trees, soil, etc.), it would have to “pre-pay” for a credit demonstrating that the organization (or a third-party) had already removed and sequestered an equivalent ton of carbon from the atmosphere. Accompanied by an open commodity market for such “carbon removal credits,” companies would be able to comply with this policy in an economically efficient manner.

A “pre-pay” carbon pricing policy would have many benefits compared to carbon taxes and cap-and-trade policies. For one, “pre-pay” systems are intuitively fair. If a company removes an equal quantity of a pollutant that it intends to emit before it actually creates that pollution, then the company can make a strong case it is doing no harm to the environment on net. Second, a “pre-pay” policy would be administratively simple. Unlike existing cap-and-trade program designs, a “pre-pay” system has no need for setting rules about allocating emission allowances, banking/borrowing of allowances, and the use of offsets. Third, a “pre-pay” system provides a political middle ground that enables both fossil energy and environmental advocates to achieve their goals, as a “pre-pay” policy would neither kill fossil energy nor enable business-as-usual when it comes to carbon emissions. Instead, a “pre-pay” carbon policy would let the market decide whether it is more economically efficient to transition to non-fossil sources of energy or to pay for removal credits needed to continue using fossil fuels. In this way, a “pre-pay” system would look similar to both an upstream carbon tax and a cap-and-trade system. Finally and best of all, this system would lead to an immediate decarbonization of the economy on net.

A “pre-pay” carbon pricing system would have a number of significant challenges to implement. For one, it would require complex border adjustments to imported goods to ensure carbon emissions aren’t simply shuffled internationally. Second, this program would need to be coupled with strong conservation policies to ensure that ecosystems were not purposefully degraded for the purpose of then “restoring” them for carbon removal credits. Third, removal credits – be they biological or geological – would have to be stringently verified for their permanence and sustainability, requiring significant and potentially complex administration (and potentially additional scientific analyses).

But the biggest challenge and reason that a “pre-pay” carbon policy will remain purely hypothetical for the near future is the cost of carbon removal approaches. Today, many carbon removal approaches are estimated to cost over $100/ton of carbon removed, which is an order of magnitude greater than other major carbon pricing programs across the world (including the EU and California). What’s more, many carbon removal systems have not been built at commercial scale yet, so it is possible that a “pre-pay” carbon policy would even be technically infeasible to achieve in the near-term.

Above: while the estimated scale potential for carbon removal solutions is large, so too are the estimated costs of carbon removal systems.

If carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs continue to languish as politically infeasible, however, we will need some way to efficiently reduce net carbon emission levels. And even if other carbon pricing systems do take off, a complementary “pre-pay” policy could prove beneficial for stimulating early commercial demand for carbon removal solutions. As such, investing today in research and development to lower the cost of carbon removal approaches and to improve the efficiency of monitoring and verification efforts would have an enormous payoff if it led to a politically feasible “pre-pay” carbon policy.

How today’s “low-carbon” investors are charting a course for financing tomorrow’s “negative-carbon” investments

In 2014, investors allocated $310B in capital to clean energy projects according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, making up a significant portion of the ~$1.5T in total global investment in energy supply as estimated by the International Energy Association (“IEA”). What’s more, the IEA predicts we will need over $40T in cumulative energy investment by 2035 to meet energy needs, suggesting that the amount of capital needed to be deployed annually for clean energy projects will have to increase by an order of magnitude over the coming decades to meet the dual goals of preventing climate change and powering the world’s economy.

Above: The IEA’s 2014 World Energy Outlook projections for necessary clean energy investment.

As the clean energy finance community grows, it also pioneers new ways to finance low-carbon energy projects. The past few years are no exception: publicly-traded yieldcos have flourished, asset-backed securitization has helped reduce cost of capital for distributed generation companies, and public-private partnerships have helped increase clean energy deal flow.

These financial innovations that enable low-carbon projects have enormous implications for “negative-carbon” projects that scientists increasingly project we will need but that have only just begun to develop. Low-carbon technologies like energy efficiency and renewable energy have had several decades to de-risk technical, regulatory, and financial barriers, and sit well poised to expand rapidly. Negative-carbon approaches must leverage as much of the experience of low-carbon projects as possible if they are to develop to appropriate scale quickly enough to prevent climate change.

Later this month, many low-carbon financial success stories will be on display at the Low Carbon Energy Investor Forum 2015 in downtown San Francisco. I’m excited to be speaking at the event, as the agenda includes conversations on emerging financial innovations, technology developments, and policy support needed to scale low-carbon developments.

What is particularly interesting to me about this, however, is that for an event with the words “low carbon” in the title, the word “climate” appears only once on the agenda — for a session titled “Climate Change – The new factor becoming mainstream among investors.” This shows that, with or without an explicit mandate to fight climate change, the financial sector is committing hundreds of billions of dollars to technologies that are pivotal for fighting climate change. And as much as any financial lesson, negative-carbon solutions can learn from low-carbon solutions the power of strong financial business cases in helping to catalyze the growth of negative-carbon solutions, and make these nascent investments today the “mainstream” investments of the future.

Want to join the Low Carbon Energy Investor Forum? Use the code “lcei15” for a 15% registration discount.

Weekend Links

Pathways to carbon-removing energy:

- Commercial use of direct air capture machines for fuel synthesis can help pave the way for negative-emission direct air capture and sequestration projects. This news about the air-capture/fuel-synthesis collaboration between Audi and Climeworks is an encouraging sign.

- Thermochemical conversion of biomass also provides an important route to carbon-removing bioenergy + carbon capture and storage. This project in France led by energy major Total isn’t planning to capture carbon emissions, but the learning from this project will be critical for future efforts that do incorporate capture systems.

- Bioenergy + surfing for carbon-removing energy systems? Very cool.

- Progress at Berkeley on nanotechnology for artificial photosynthesis

Agriculture and Forestry:

- A blueprint for low-carbon agriculture in California with a number of carbon-sequestration recommendations

- The USDA also released its “building blocks for climate smart agriculture and forestry“

- Providing incentives to restore Grasslands requires measurement and verification protocol, like this one recently released by the Climate Action Reserve.

- Reforestration project takes off in Misssissippi

- ClimateProgress on the soils and climate change.

- China’s Great Green Wall projectholds potential for large scale afforestation, but many questions remain unanswered about its long-term impact.

Other:

- The potential role of carbon removal as a complement/enabler of continued fossil fuel use has the potential to grow highly contentious in coming decades. John DeCicco provides an interesting perspective on this conversation.

Throwing the Carbon Capture Baby out with the Coal Bath Water

The environmental advocacy group Greenpeace recently released a report lambasting carbon capture and storage (or “CCS”) as “a false climate solution” that “[i]n no uncertain terms…hurts the climate.” The Greenpeace analysis, however, made a number of assumptions that fit the conventional wisdom surrounding CCS, but when analyzed with greater scrutiny turn out to be deceptively misleading.

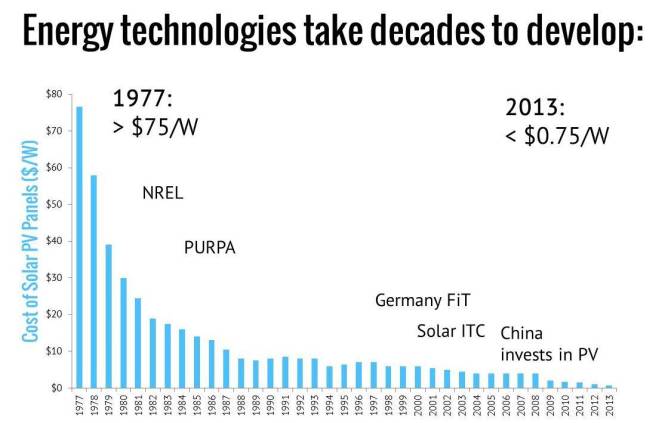

Misleading Assumption 1: CCS requires that we prolong coal use. Can we have CCS without coal? From a technical point of view, of course. The California Energy Commission just held a workshop on natural gas power generation and CCS, a handful of companies and researchers are working on direct air capture systems that can pull carbon from ambient air, and researchers across the globe have begun thinking about carbon-negative bio-energy and CCS projects. It may be politically infeasible to start developing CCS on these non-coal resources, but a compromise could be to ensure that we phase out coal CCS in favor of non-coal CCS. Regardless, it’s too early to say whether these non-coal (and even renewable!) CCS systems can play a large role in fighting climate change, because we simply have not done enough research and development to have good data on these systems. Throwing out renewable CCS today as the unrealistic dreams of “techno-optimists” is analogous to stopping the development of solar energy back in the 1970s because it was over 100 times more expensive than it is today.

(Update: presentations from CEC workshop on natural gas + CCS available here.)

Above: Data from Bloomberg New Energy Finance

Misleading Assumption 2: It is inevitable that CCS will lead to increased EOR. Can we do CCS without EOR? Yes. There are a number of demonstration plants across the world injecting CO2 underground that involve no EOR. If we don’t want EOR, we simply need to regulate CCS so that it can be cost-effective without additional fuel production. Such a pathway will increase the cost of CCS, and there is a much more valid and nuanced debate than what the Greenpeace analysis provides on whether we should pursue EOR in combination with CCS that focuses on using EOR as a pathway to net-negative emissions. But if we wanted to assume that EOR was entirely undesirable, we could still have CCS — it would just cost more than it would in conjunction with EOR.

Misleading Assumption 3: Underground storage of carbon is required for sequestration. Does carbon have to be stored underground? No. We can turn it into cement, plastics, or any number of other solid products. Will there be issues with storing large volumes of solid carbon above ground? Probably. But we can get around the geologic sequestration problem if we wanted to accomplish this goal.

So can CCS hurt the climate if done wrong? Certainly. But is Greenpeace justified in saying that “in no uncertain terms” CCS “hurts the environment?” Certainly not.

As a result, I remain unconvinced that we should throw out CCS as a climate solution today. Instead, environmental advocates should strive to make clear all of the potential pitfalls of CCS, and ensure that its development balances these environmental and social concerns with the economic considerations of the companies and regulators responsible for deploying these solutions. If you think coal is bad, fight coal. If you think EOR is bad, fight EOR. If you think geologic sequestration is bad, fight geologic sequestration. But we can make a world where coal, EOR, and geologic sequestration do not exist but where large-scale CCS still flourishes if we so choose. While this world might seem far from reality today, it might be the only world where we can prevent catastrophic climate change, as most renewable energy solutions (like wind, solar, geothermal, etc.) are not capable of generating the net-negative emissions we likely need to prevent climate change.

Above: adapted from the Climate Institute “Moving Below Zero” report

So let’s stop entangling CCS inappropriately with arguments against related energy systems, because we can decouple CCS from these system is we choose. If we keep conflating CCS with these other arguments, we risk throwing out the CCS baby with the coal bathwater.

“Legacy” Emissions and Beyond-Neutrality Corporate Emission Reduction Targets

Summary:

- Corporations need not only to stop emitting greenhouse gases (“GHGs”) to prevent climate change, but they also need remove and sequester “legacy” emissions from the atmosphere.

- Corporate GHG emission reduction targets set at levels above 100% create new challenges for corporations around measuring their past emissions, setting appropriate targets, and deploying strategies to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

- Despite the challenges, the new opportunities for value creation from carbon removal for corporations are significant.

—

Post:

A number of large companies have recently introduced pledges to eliminate carbon emissions entirely in their efforts to fight climate change and grow in a sustainable manner. While eliminating future emissions is an important first step on the pathway to stabilizing our climate, few companies are talking about how they can deal with the fact that a significant percentage of their emissions from previous decades of doing business still remain in the atmosphere, contribute to climate change, and affect the sustainability of their operations going forward.

Scientific context. Carbon dioxide is considered a “long-lived” pollutant, meaning that it resides in the atmosphere for centuries (on average). This leads to a pesky problem — we could decarbonize our economy entirely, and we still could face the consequences of climate change caused by pollution from decades past. As a result, it is increasingly likely that we will need to employ carbon removal solutions — i.e. processes capable of removing and sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. While there is increasing activity to develop such carbon removal solutions, proven and scaleable carbon removal solutions have yet to emerge.

Challenges for corporations. Carbon removal creates a number of challenges for corporations seeking to set meaningful GHG emission reduction targets.

- Measurement. It is frequently difficult for companies to asses their historic contributions to carbon emissions. Companies can usually get a rough order-of-magnitude estimate of historical emissions, but it is very difficult to tell using legacy systems that might not have captured necessary data to get a more precise estimate.

- Targeting. Even if companies have a good sense of their total historical emissions, it can be difficult to set reduction timelines. New science-based methodologies are being developed to help inform forward looking targets, but it is unclear whether they will incorporate negative emissions. A more fundamental question is how companies might deal with legacy emissions not directly attributable to them, but that still affect how they do business in the future.

- Action: Given the current state of development of many carbon removal approaches, companies could face challenges around generating scalable and verifiable net-negative emission levels. Many carbon removal approaches today are expensive to deploy and/or measure, so companies are unlikely to deploy these such technologies at scale without further development.

Opportunities for corporations. Despite the challenges associated with adopting greater than 100% emission reduction targets, corporations that strive for such targets stand to seize valuable business opportunities — even in the sort-term.

Above: data from the CDP 2012 disclosure scores, with my own analysis of carbon removal potential.

For one, carbon removal offers new growth opportunities for companies thinking about providing carbon-negative products and services. Today, startups like Newlight Technologies are developing carbon-negative plastics that can substitute directly for carbon-emitting products — similar carbon-removing products could provide a great way for companies in commoditized industries for differentiating their offerings.

Above: AirCarbon packaging used by Dell. Source: packworld.com

In addition, carbon removal solutions can help improve operational and supply chain efficiency. For example, agricultural carbon removal solutions such as restorative farming approaches hold the potential for increasing crop resilience, reducing water and fertilizer needs, and even enhancing yields.

Above: biochar field trials. Source: International Biochar Initiative.

Lastly, corporations that move early to set net-negative emission reduction goals stand to generate large brand leadership benefits. Consumers are hungry for innovative climate solutions, and are likely to reward corporations for their leadership in enabling consumers to vote with their wallets for carbon-removing products and services. With strong corporate leadership and academic partnerships, we could start seeing carbon-negative products across numerous industries, including: foods, cements, fertilizers, and even gasoline.

Moving forward. It is clear that companies still have a long way to go just to get to carbon neutrality. But it is important for corporate managers to think about how the long-term pathway to sustainability might involve net-negative emission reduction targets, and how early movers can start generating value through carbon removal today. Right now, little changes in reporting standards and protocols could go a long way to achieving this potential. For one, the CDP could update its Leadership Index and the GRI could update its reporting guidelines to encourage companies to employ net-negative emission strategies. In addition, the LEED green building rating system could encourage the use of more carbon-removing materials. But most importantly, early corporate leaders will have to stand up and commit to a “beyond-neutrality” goal, and show that it is possible to make steady progress towards that goal with a combination of the mitigation technologies of today and the carbon removal solutions that hold promise for our future.

Carbon-as-a-service Businesses?

The Cleantech Group’s annual San Francisco Forum wrapped up earlier this week. The event’s theme was “Cleantech-as-a-service,” and featured parallel tracks named “Cloud” and “Connect.” Overall, this focus on technology-enabled business model innovation shows how mature the cleantech field has become, as the event felt very much like a “standard” tech conference in the Bay Area.

Above: Sheeraz Haji kicking off the Cleantech Forum SF 2015 event.

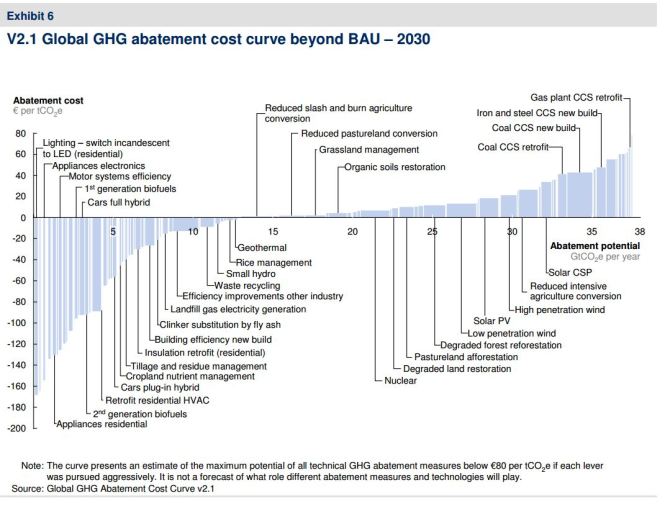

The growing emphasis on the “tech” portion of “cleantech,” however, has not caught on for all clean technologies. For example, carbon sequestration businesses were conspicuously absent from this year’s Forum. Economic fundamentals can help explain this lack of carbon sequestration businesses on display. Most of the discussion at the Cleantech Forum focused on the left-hand side of the McKinsey GHG abatement curve (below), which makes perfect sense: no amount of clever business model or financial product innovation will help uneconomic businesses (like many carbon sequestration businesses today) flourish.

Above: McKinsey GHG Abatement Cost Curve

The big exception to the above, however, is solar PV — which many would call the poster child of the cleantech-as-a-service revolution. What has set solar apart from other high dollar-per-ton GHG abatement schemes is non-carbon-focused regulations (be it some combination of net-metering, renewable portfolio standards, PACE financing, etc. designed to specifically support renewables).

What is so striking is how little acknowledgement such policies now get in the cleantech conversation. Business model innovation is highly complementary to environmental policies, yet so few of the leaders on stage at the Forum advocated for additional/ongoing policy support. I worry that the focus on business model / financial innovation will only take the cleantech field so far (or will delay its development considerably), preventing us from achieving the rates of decarbonization necessary to prevent climate change.

When former EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson came to speak at Berkeley on March 12th, she remarked that her job at Apple today is still to make good policy, it is just to do it from inside of business instead of inside government. I am eager to see if this philosophy will gain broader acceptance, and I look forward to the discussion at future Cleantech Forums to track how this dialogue unfolds.

How weight loss can put carbon removal in perspective

Six years ago, then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton compared climate change to weight loss:

“You know, oftentimes when you face such an overwhelming challenge as global climate change is, it can be somewhat daunting,”

and,

“If we keep in mind the big goal, but we break it down into baby steps – those doable, achievable objectives – we can do so much together.”

Clinton’s analogy comparing fighting climate change to weight loss can be extended to help put carbon removal in context. In this analogy:

- Conservation and mitigation: analogous to going on a diet. The no-brainer strategy for starting to lose weight is to eat fewer calories, just like the no-brainer strategy for preventing climate change is to reduce carbon emissions from activities such as burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and intensive industrial agriculture.

- Removing carbon from the atmosphere: analogous to exercising. Sometimes diet alone isn’t enough to lose weight, exercise is needed too. In the same way, simply stopping carbon emissions might not be enough to prevent climate change — we might also need to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere and/or oceans. And even if we could prevent climate change without carbon removal, pursuing carbon removal strategies slowly and in moderation is likely to be beneficial regardless, much in the same way that moderate exercise is healthy regardless of whether it is necessary for weight loss.

- Adapting to changes in the climate: analogous to buying new clothes. Buying new clothes does nothing to help you lose weight — but it does make like more comfortable while you are overweight. No doctor has ever said, “it’s OK to be obese — you can adapt to this condition by planning what new clothes you should buy as you grow larger…” just like scientists largely agree that climate adaptation is no substitute for preventing climate change in the first place.

- Albedo modification geoengineering techniques: analogous getting lap-band surgery. Lap-band surgery can have devastating side effects and so is only recommended in extreme circumstances. What’s more, the procedure only works in conjunction with diet and exercise. In the same way, albedo modification geoengineering techniques are viewed as highly risky and uncertain, and require dramatic emission reductions and carbon removal for them to be phased out.